common dodder

The common dodder is an annual climber that is a relative of the morning glory. It is an obligate parasite which means it takes everything it needs to grow and reproduce from another plant, often causing the demise of its host. It is native to most of North America, and is naturalized in Central Europe. Masses of its yellow to orange stems are most often draped over plants in sunny but moist habitats such as damp thickets, floodplains, roadsides, and swamps.

Like many other annual plants, the precise locations of dodder plants are not predictable from year to year at Salter Grove. However, the yellow-orange tangles of common dodder are reliably observed along the causeway and the Marsh Trail starting in July. Within the park, observed host plants include American pokeweed, Japanese knotweed, jewelweed, maritime marsh elder, and the seaside goldenrod.

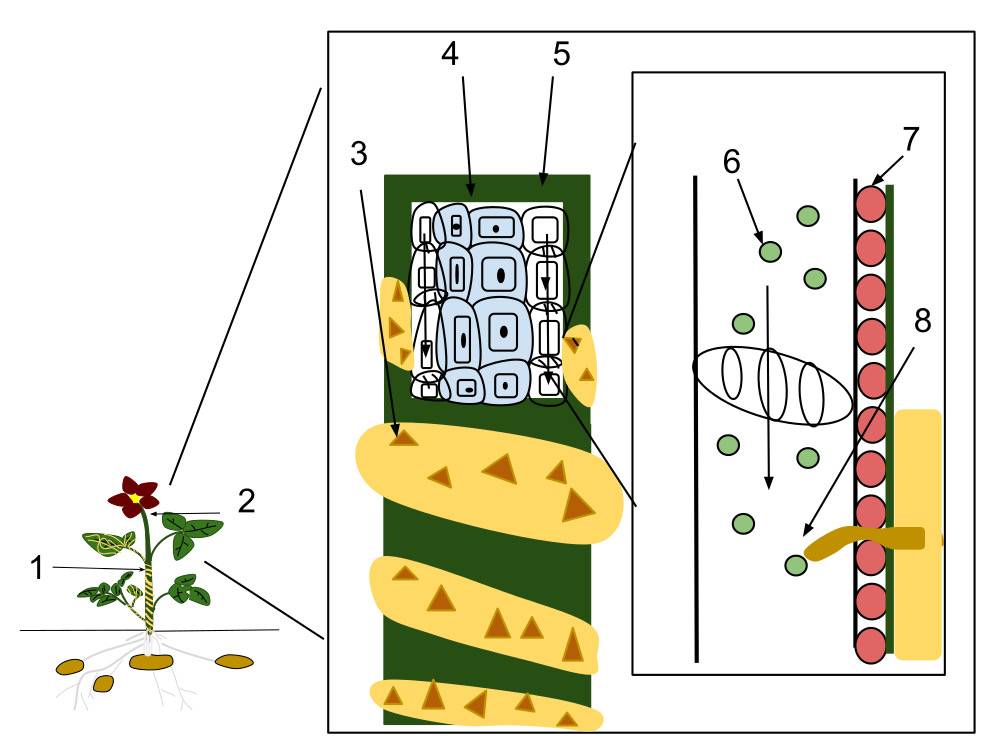

Dodder seedlings start with roots but dispense with them once the stem achieves a physical connection to a host plant. Small sections of the twining dodder stem develop into haustoria (or haustorium, when singular), projections that are capable of penetrating the host's phloem tissue to commandeer nutrients for its own use. As the dodder stems grow they continue to invade more host tissue and will even latch onto neighboring plants. Dodder leaves are present as barely visible scales on the stem, and although containing small amounts of chlorophyll, do not engage in photosynthesis much. The small white flowers are visited by wasps. The fruits develop as rounded yellow-to orange capsules, each containing four seeds. Once the seeds fall out of the capsule, the main agent of dispersal is by water.

Choice, and timing of establishment on a host plant will determine whether a dodder plant succeeds in producing seeds. The selected host plant must be sufficiently robust to support the dodder through flowering and fruit production. Landing on too small a host plant may lead to an early end for both the host and parasite. Growing too many parasitic stems before flowering may weaken the host's ability to support the dodder through seed reproduction.

The Cherokees used dodder as a poultice for bruises. Other medicinal uses include treatment for muscle pain and rheumatism. The plant is also used to prepare colorants for yellow, gold and green. The common dodder is seriously detrimental to cranberry production in Wisconsin. Growers report up to a 50% reduction in yield and are frustrated because there is no easy way to eliminate the infestation.